'To love life even when you have no stomach for it' By Madeleine Alice

The Ninth 'Letter from a Caregiver.'

Hello, dear Friends. In our ‘Letters from a Caregiver’ collaboration, we’re sharing heartfelt messages of wisdom and comfort to our younger selves.

Our Letters

Introduction and letter to my September 2017 self by Victoria

'Strength in Vulnerability; Growth from Adversity.' By Dr Rachel Molloy

“Changes beyond my control but agility beyond my imagination.” by Victoria

“From The Other Side Of The Story.” by The Invisible Caretaker

“Healing Comes in Many Forms: Honoring our Sacred Contract” by Janine De Tillio Cammarata

Lessons from the one who knows us the best

The uncomfortable truth is that while we may seek belonging—for others to understand us completely—they can maybe walk in our shoes for a little while, but they’ll never live in our skin and feel what we feel wholly, over our lifetime.

We are the culmination of nature and nurture, millions of choices and decisions, evolution, circumstances, and learning. We’re wondrously unique.

AND we’re also social animals, seeking community and connection, trying to relate to one another and bridge any divides or dissonance to be part of something —not alone.

Just when we think we’ve cracked the code of belonging, life happens, change erupts, and as Bruce Feiler1 says, we experience a lifequake. A disruption is one form of transition. A ‘lifequake’, as it suggests, shakes, discombobulates and rearranges our way of life.

We lean on family, friends and our ‘chosen family’ where and when we can, but ultimately we have to figure out how to navigate the new fault lines. Every quake, disruption, and transition has a before and after, a loss and a new way of being.

The spin cycle of navigating Dad’s health nightmare and my job, in 2015 (you can read about it here A Prelude to Caregiving: Love and Torture) was lifequake number 7.

For me, each lifequake was a lesson in humility, resilience, and self-compassion, as well as in creating space for change. It’s messy and uncomfortable. There’s grief within that change: what was, and what can’t be.

The lived experiences of lifequakes are a great connector; life’s natural compost for empathy to thrive, and for us to grow.

When I read Madeleine’s post, ’EverGrief: A Beginning. The who, what & why behind EverGrief,’ my heart and head connected to her expressions of grief; grief that is overlooked, invisible, or less understood - ie disenfranchised.

“I write about the multitude of loss that occurs within a body that is chronically ill, in a world that expects recovery. What I have found though, is within this very personal well of heartbreak, it has cracked me open to the underworld of losses that we all face everyday and yet do not have the language, and with it grace, to validate & honour.” Evergrief, Madeleine Alice

In this ‘Letters from a Caregiver’ series, connecting to our younger selves gives us a unique opportunity to soothe the grief we carry and reconcile with what was and what we’ve had to navigate. Hopefully, we receive the comfort we need from the one who knows us the best, ourselves.

Within the heart of Madeleine’s letter today are these lines:

“Change will become the only certainty you know, and in that constant transition, loss will be the other guarantee. But you’ll come to see these not as punishments, but as invitations into life. Each change will ask you to live more honestly with what is.”

Inspiring words of courage. A reframe towards hope.

Thank you, Madeleine.

Author: Madeleine Alice (she/her) is a writer and grief tender based in the UK, with a background in counselling skills, Yoga Nidra facilitation, and Death Doula training. Her work is ever-evolving and rooted in trauma-informed care. Trained in a range of supportive modalities, Madeleine offers guidance for those navigating life’s many endings — from illness, relational breakdowns, and identity loss to environmental grief and death.

Through her Substack, Evergrief, Madeleine explores the living landscape of loss and the many forms of grief that often go unseen or unacknowledged by society. Evergrief speaks to the ongoing griefs of chronic illness, identity shifts, and life’s complex thresholds. Madeleine tends to the endings that rarely have rituals, yet shape us all the same.

To love life even when you have no stomach for it

Dear you,

There’s so much you don’t know yet about life. You are about to turn twenty-one and your life is going to radically change. You are on the threshold of adulthood, you are on the threshold of diagnosis. Right now, you believe strength means holding everything together. You don’t yet know how much life will ask you to let go. I know right now you are wishing things would change, and yet change is the very thing you’re most frightened of.

There will be seasons when you no longer recognise yourself, when identities you built your belonging around fall away, and no one else notices they’re gone. You’ll try to talk about it, but the language won’t land. This is disenfranchised grief, the kind that has no funeral, no ritual, no name. The kind that asks you to carry it alone.

You’ll come to see that there are many kinds of dying. Most don’t come with ceremony. You won’t recognise them in the moment, apart from that familiar ache in your chest. You’ll come to believe you’re too sensitive or too much, but really you’re just feeling the truth of endings.

These deaths happen within you, as you are changed by life. There will be times when you know there’s no going back. You will forever miss those parts of you deeply.

There are other deaths too, the spaces between people, the way they come and go from your life. Sometimes through heartbreak or friendship breakdowns. But there are quieter endings, the slow, painful experience of being forgotten, of memories once held by two people now remembered by only one. Grieving someone who is still alive will be one of the most painful experiences you live through. It will tear your heart open again and again.

You’ll lose homes. You’ll lose yourself. You’ll feel left behind by life, as if you’ve fallen through time, lingering between what was and what could have been. The pain will feel so intense, sometimes you’ll forget how to breathe.

You’ll learn that not everyone is who they appear to be. Often, your own yearning for who they could be will blind you to who they actually are. This will cause many relational ruptures, your heart will break with every ending.

Your life is full of worth, even when it’s confined to your home. Your health is dynamic; just because it changes in appearance doesn’t make it any less true. Grief and chronic illness are so entangled… you are allowed to claim that, you are allowed to wish it was different.

These are all living losses. They shatter your heart in very real ways. They are the fabric of your life. You are allowed to mourn. It’s okay that you feel hopeless some days. It’s okay that the pain in your chest feels like it might consume you.

For years you’ll deny these truths. You’ll force the pain down.

When you conjure the courage to speak of your grief, it will often be dismissed. When you reach out for help, your heartbreak will be placed low on the hierarchy of loss. You’ll begin to internalise it, and blame and shame will saturate your inner world. You’ll feel you have failed. You’ll ask, why can’t I just move on? That will be one of the most painful questions you ruminate on.

You won’t find refuge in many places. But the one place you will find is within yourself.

You’ll learn, slowly, to make your own rituals for what’s been lost, to light candles for what’s left unspoken, to hold your own hand when no one else sees the weight you’re carrying.

Change will become the only certainty you know, and in that constant transition, loss will be the other guarantee. But you’ll come to see these not as punishments, but as invitations into life. Each change will ask you to live more honestly with what is.

And once you are changed, you are allowed to mourn what was. There will be days when the ache of what you’ve lost feels unbearable. Don’t rush yourself through it. Don’t try to force the shape of what’s next. You can’t bypass what is.

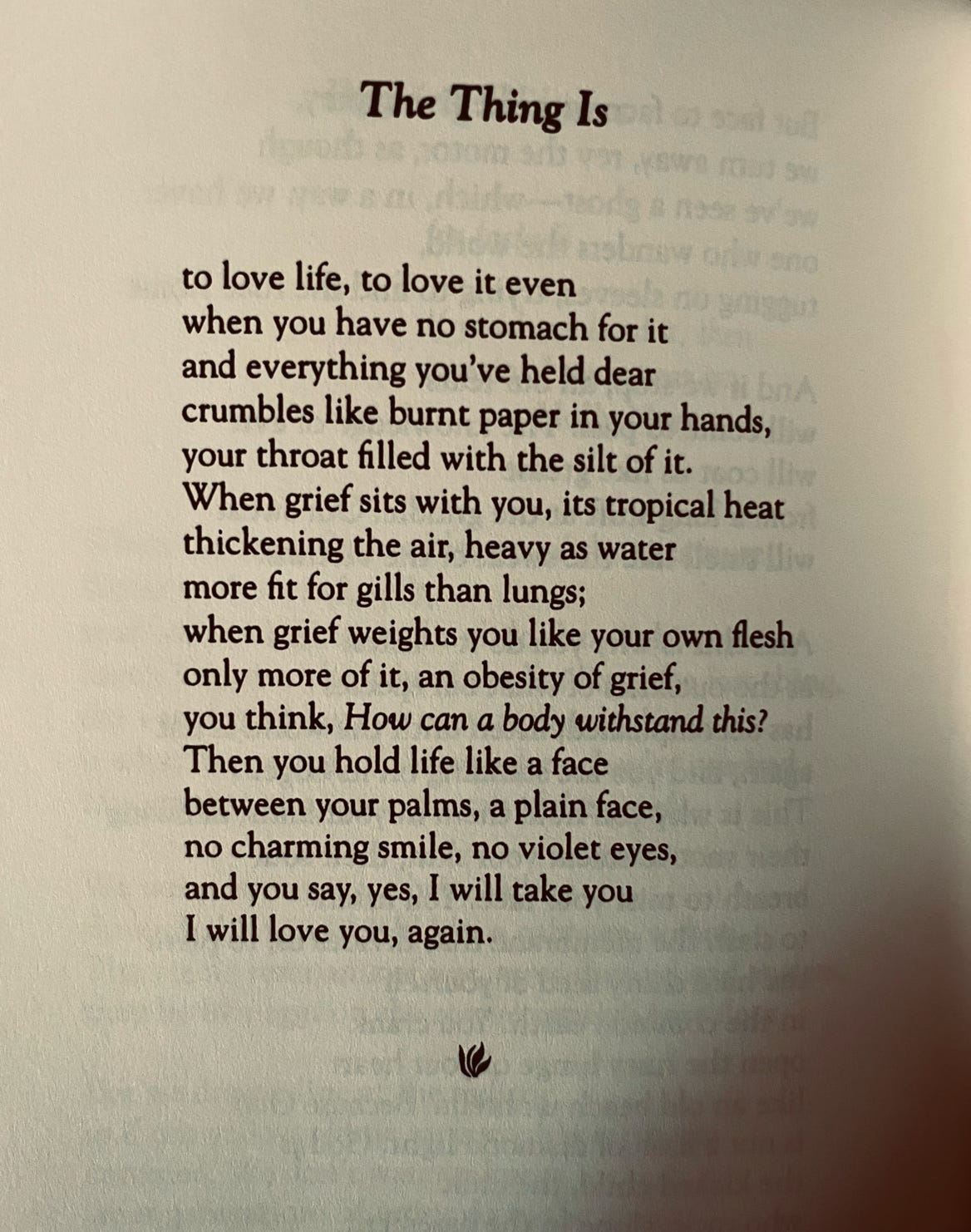

That opening, painful as it is, will also bring new things into your life. Slowly, you’ll find ways to accept what is happening. You’ll begin to touch more aliveness; what once felt dulled will become more vibrant. You’ll develop a love for what is. As Ellen Bass writes, to love life, even when you have no stomach for it, becomes your daily practice. You’ll take life in both hands and say, I will take you. This is intimacy with life.

Each day your compassion for yourself will widen. You’ll realise you are moving toward taking better care of yourself, honouring your needs, toward meeting people where they are instead of where you wish they would be.

And through all of it, you’ll begin to understand that grief isn’t something to overcome. It’s a companion, sometimes quiet, very often demanding. It will carve you into someone who notices more, who loves differently; someone who knows how to stay with what’s hard.

No matter how much you learn, you’ll wish none of it had happened this way.

And then, one day, you’ll write a letter to yourself, not to explain it away, but to recognise the one who walked through it without a map. You will begin to understand that what lies beside the deepest pains of your life is something so vast, so expansive, that words will never touch it. You’ll finally see that all these years you have been tending to the land of the soul. And you have been made into one who walks toward the life that still lives here.

The Closing Rapid-Fire Questions to Madeleine from Victoria:

What is empathy to you?

Empathy, to me, is taking the time to truly listen to another’s experience, with full presence and awareness of my own projections. It’s listening deeply enough to understand not only what is spoken, but also what remains unsaid. Remaining willing to be changed by the role of witness.

What’s one question you’d ask your future self?

How has your relationship changed with acceptance - what does it look and feel like to you?

What’s one quote/song/movie/book that carried you through today?

“Silence is a practice of emptying, of letting go. It is a process of hollowing ourselves out so we can open to what is emerging. Our work is to make ourselves receptive.” - Francis Weller, ‘The Wild Edge of Sorrow.‘

Dear reader, what losses in your life have gone unacknowledged, yet shaped you deeply?

Please ‘❤️’ LIKE the article & consider subscribing!

Carer Mentor by Victoria is free to read. If you have the means and would like to support the publication, I welcome monthly (£6) and annual (£50) subscriptions. Thank you for your ongoing support.

© Carer Mentor, October 30, 2025. This concept/theory/poem is original to Carer Mentor™ VLChin Ltd. If you use it, please give credit and link to the original work. Thank you. www.carermentor.com

Bruce Feiler’s website, the book I refer to: ‘Life is in the Transitions. Mastering Change at Any Age.’ His TedTalk. The article I wrote transcribes key points of his talk.

Oh my goodness, Madeleine. The deeper I got into your letter, the more the hair on the back of my neck stood up. The unfolding of self-awareness, particularly around self-care really resonated with my journey. So many great insights. "Right now, you believe strength means holding everything together." Oh, yes. Coping through putting on armor to shield me from what was happening. "Lingering between what was and what could have been." I lingered alright, but mainly in anger at the universe. And there were days when that anger ate at my insides.

And then, "you'll realise you are moving toward taking better care of yourself, honoring your needs, toward meeting people where they are instead of where you wish they would be." A profound change in point of view, in my case trading anger for compassion.

"You'll finally see that all these years you have been tending to the land of the soul."

Wow. Mic drop.

Thank you so much for sharing this.

I have never felt so isolated and alone as when I was caring for my dying husband in 2020. It felt like our family and friends almost couldn't fully believe what was happening. And neither could my husband. He didn't even look ill, until a couple of months before he passed. He acted like he had a bad case of the flu, spending his last months revising a will and securing money for the kids. I followed this lead and worked 16 hours days for the government managing the COVID response in Seattle.

We had a one good cry together when the doctor finally said, there's nothing more we can do. That was it. He stopped talking the last couple of weeks before he died. I didn't have closure, no service, no peace. I noticed the calls and inquires dying as well, just a month after.

People are not comfortable with death so they avoided me and my pain. I carried resentment for a couple of years but knew this wasn't good for my body or soul.

Grief doesn’t disappear when you bypass it. It waits. It settles into the body like an echo, and it stays there until you’re ready to feel it. I feel like I'm letting mine guide me, when to release, when to sit with it. We need more people to share their stories of loss and illness like you did so beautifully. Thank you.