'Grief is messy. It's not a tidy five-stage path.'

Shankar Vedantam interviews Lucy Hone (Public Health Resilience Researcher).

Summary:

Lucy Hone, a public health Resilience Researcher, shares her insights on grief following the loss of her daughter. She draws on her experience as a resilience researcher to support and analyse her own grief journey. She differentiates between grief reaction, which is uncontrollable, and grief response, which involves active choices to manage grief and having more personal agency. Hone emphasises the importance of oscillating between confronting grief and taking a break from it, a concept known as the oscillation theory. She also discusses the significance of making conscious choices about what to focus on, asking oneself whether a thought or action is helpful or harmful. Hone encourages people to seek serenity, pride, or awe - feelings that we associate with being part of something bigger, and to understand that suffering/adversity is a part of life, which can prevent feelings of victimisation. She argues that grief doesn't shrink over time, but life grows around it. ‘Grief is as individual as a fingerprint.’ Experiment and walk the grief journey in a way that feels right for you.

I recommend listening to the Podcast from the beginning to appreciate the context of Lucy Hone's experience. Below, I'm highlighting the most impactful podcast clips and messages that resonated with me. This interview goes beyond her TED Talk (September 25, 2019), 'The Three Secrets of Resilient People'.

Shankar Vedantam's (2022) interviews resilience researcher Lucy Hone. Lucy shares the techniques she learned to help her cope after the devastating loss in her own life

Key Timestamps and impactful insights.

This transcript was taken from the Hidden Brain Website, and edited by myself.

15.30 The question: can I go on? It all felt too hard. 'Grief Ambush' takes hold unexpectedly, and you're powerless to control or manage the emotions.

20.40 The 5 stages of grief are for other peoples comfort, they don't work. People tell you and expect you to go through them. Lucy was frustrated by the stages. Her mission was to 'Survive this'. She found the stages too passive.

'I don't want to be told how I am going to feel I am desperate to know what I can DO to help us all adapt to all this terrible loss.'

22.30 She was starting to think of herself as the researcher and the research subject, internally observing her loss and her reaction to it. Could tools from resilience psychology help? They’ve been shown to help people cope with potential traumatic events. So, could they be useful in the context of bereavement? She's been exploring this ever since Abi, her daughter died.

24.00 Pondering this question gave her the space to analyse how her own mind was responding to grief.

When she noticed something about how she was coping, she reserved judgment about what it meant. When she engaged in what-if scenarios? She noticed how these thoughts made her feel. She paid attention to how she felt after getting exercise or a good night's sleep. In other words, she started behaving like a scientist. She eventually discovered there were things that made her feel better and things that made her feel worse. She came up with a series of techniques that gave her a measure of control over her grief.

24.45 Lucy: I distinctly remember standing in the kitchen thinking, "Seriously, Lucy, choose life, not death. Don't lose what you have to what you have lost."

25.10 Lucy is a public health researcher at the University of Canterbury. After her 12-year-old daughter was killed in a traffic crash, Lucy tracked her own bereavement process closely. She realised that she, herself, did not follow the five stages of grief. She also realised that we are wrong when we think grief is only something that happens to us. While it's true that grieving people do not feel they have much control over their emotions, there were things she could do to change the way she felt. They were active choices she could make. These choices did not erase her grief. That was neither possible nor healthy. But they did allow her to feel like she could manage it.

A difference between her reaction to grief and her response to it.

26.01 You have little control of your Grief Reaction and all its physical symptoms that occur when we are bereaved: aching, grief sweats, nighttime sweats, and the torrid roller coaster of emotions.

But we do also have the Grief Response, which is about how we choose to respond to the grief: the ways of thinking and acting and the micro-choices we make all day long, that help or harm our grief. So while we can't control our grief reaction, our grief response is pervaded with choice.

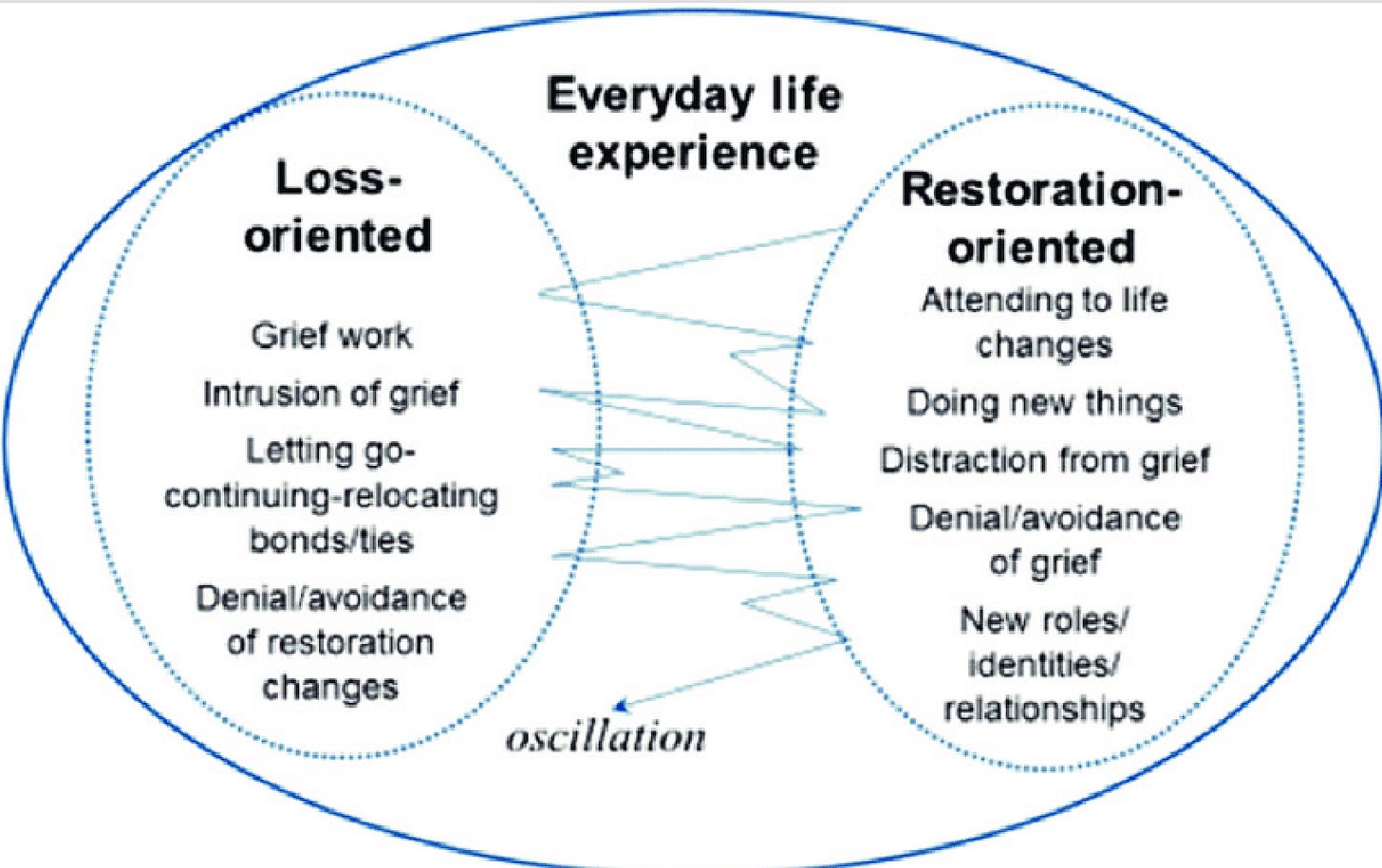

27.00 The work of Columbia University researcher, George Bonanno 'most people get through grief on their own without medical/clinical intervention. M Stroebe and H Schut 'The Oscillation Theory'1

George Bonanno's work (reference below) gave Lucy hope. Margaret Struber and Henk Schut.'s oscillation theory is a different model of grief: approach grief, and then it's okay to withdraw from it, and take a break. That is not avoidance/denial, but actually a healthy way to grieve.

One is loss-oriented and the other is restoration-oriented. You fluctuate between coping with the loss and the restoration - "who am I now and how will I learn to live without this loss? You ebb and flow between these two processes, dynamic process. We needed to take breaks from our grieving process, and that's where positive emotion can come in too.

29.56 It's important to choose where you focus your attention. Grief is full of choices. Ask yourself "Is doing that going to help me or harm me in my quest to survive this loss?" I was putting myself in the driver's seat and taking back a bit of control.

32.37 When people are experiencing grief, we expect them to follow scripts. By taking back that narrative, you can start to make choices that craft your own journey. It may be a different choice than others, but it's important that each person exercises the AGENCY to make the choice that best fits their mental makeup and psychological well being.

We all grieve differently. Grief is as individual as your fingerprint.

There's actually very little evidence that says that we go through those five stages. They have been perpetuated, because they're a tidy model . We're all drawn to them because in a torrid time it makes those suffering AND health practitioners feel better. But actually grief's not like that. It's messy and untidy. And in our work, people rarely say that they go through those stages.

35.11 Shankar: It's worth pointing out this is not easy to do. These are human reactions. And I want to flag that while making conscious choices about what to focus on does make sense, that doesn't mean that it's always easy to do.

"This isn't easy, but it is possible." Lucy says, 'I think it comes down to, for me, my motivation for survival was huge’.

36.33 Shankar: Lucy thought back to her days as a graduate student studying resilience at the University of Pennsylvania. At one point, her professors worked with the U.S. military to develop a resilience training program for a million soldiers. That program was based on the same underlying idea, "Pay attention to where you pay attention." You need to be aware of the way your thoughts and actions are combining, question whether the ways you are thinking and acting are working for you or working against you, positive psychology. It's important for people to find the language that works for them.

38.44 Lucy wrote a book titled Resilient Grieving. The "Why me?" question was explored in the book and TEDTAlk (3 Secrets of Resilient People). It's counterproductive. She illustrated that adversity doesn’t discriminate, everyone suffers. As much as we don't want this to be true, terrible things happen to us all. And knowing that makes it so important to understand how you react in tough times and to understand the ways of thinking and acting that can help you navigate your darker days. [Carer Mentor Note - see Emotional Agility work by Susann David}

40.14 Shankar: You say that resilient people understand that bad things happen, that suffering is a part of life and that knowing this keeps them from feeling like victims. Can you expand on this idea, Lucy? What do you mean by that?

Lucy: Understanding that everybody suffers in parts of life, that actually very often daily, we struggle and suffer and that is absolutely part of the universal existence, stops you from feeling singled out and discriminated against when something goes wrong. But critically, it also stops you from beating yourself up when things go wrong. And so when we live in an era of perfectionism, it's so important for people to understand that "Yeah, we all stuff up and do things wrong all day long and that doesn't mean we need to be punished. It doesn't mean we are useless. It just means we are human."

41.15 Shankar: The approaches are confirmed by modern, empirical, scientific tools, but they really are age-old ideas. We did an episode about stoicism with a philosopher, William Irvin, and he had this great line, "Do what you can with what you have, where you are." 'We always encourage people to focus on the things that matter and the things that they can control.'

42.30 Shankar: As Lucy looked for ways to apply these insights in her day-to-day life, she started to seek opportunities to find serenity, pride and awe. Is it possible that some people resist doing those things, because they feel guilty about doing them? We feel compelled to follow the scripts presented to us about how we're ‘supposed’ to grieve and deal with loss and trauma.

Lucy: Exactly. people feel judged and feel guilty for experiencing any form of positive emotions, that if you're experiencing positive experiences, there's something wrong with you, when actually we know that is so far from the truth.

44.39 Shankar: Some people interpret your work as pushing people at the lowest point in their lives to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, that grieving people need to be responsible for their own emotional recovery. Is that an accurate representation of your work?

Lucy: No. A very deliberate point in resilient grieving to say to people never am I trying to put more pressure on the bereaved. All of our work is created for people who come to us saying, "Thank you for validating my desire to be an active participant in my own grief journey." And so we know that so many people now are looking for ways to support them through that adaptation to loss. We are not forcing people. "These are all of the theoretically sound and scientifically backed strategies that we've come across. Try some of these out for yourself. See what works for you. Be your own personal experiment and find the grief journey that works for you." So I think that giving people a prescription for hope, I think, is the number one aim of our work.

46.23 The bereaved often think that their grief, will shrink over time. But what really happens is that your grief stays the same and your world, your life grows around it. Seven years on from Abi's death and I can notice how our world has grown beyond her. And so I can see that life literally has grown around her and our loss. We'll never forget her, but life grows and goes on. And as long as she's with us and we have her legacy, then I don't want to say that's okay, because it's not, but I guess it's good enough.

Lucy Hone is a public health researcher and practitioner in New Zealand. She's the author of Resilient Grieving, Finding Strength and Embracing Life After a Loss that Changes Everything.

Please ‘❤️’ LIKE the article & consider subscribing!

Books:

Resilient Grieving: How to Find Your Way Through Devastating Loss, by Lucy Hone, 2017.

The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us about Life after Loss, by George Bonanno, 2010.

The Resilience Factor: 7 Keys to Finding Your Inner Strength and Overcoming Life’s Hurdles, by Karen Reivich and Andrew Shatte, 2003.

Research:

Destruction to Regeneration: How Community Trauma and Disruption can Precipitate Collective Transformation, by Lucy Hone, Chris P. Jansen and Denise M. Quinlan, Wellbeing and Resilience Education, 2021.

Cautioning Health-Care Professionals: Bereaved Persons are Misguided Through the Stages of Grief, by Margaret Stroebe, Henk Schut, and Kathrin Boerner, OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 2017.

The Science of Resilience: Implications for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression, by Steven M. Southwick and Dennis S. Charney, Science, 2012.

The Dual Process of Coping with Bereavement: Rationale and Description, by Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut, Death Studies, 1999.

Other Carer Mentor articles linked to this:

Please ‘❤️’ LIKE the article & consider subscribing!

Carer Mentor by Victoria is free to read. If you have the means and would like to support the publication, I welcome monthly (£6) and annual (£50) subscriptions. Thank you for your ongoing support.

Schut, M. S., Henk. (1999). THE DUAL PROCESS MODEL OF COPING WITH BEREAVEMENT: RATIONALE AND DESCRIPTION. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

I look forward to listening to this episode! Sounds like there is a ton of excellent information packed in.

This article came at perfect timing for me, as I'm in the midst of grieving. The transcript is very helpful. I also look forward to read the previous articles you published on this subject. Thank you!