'Keep Britain Working' Report: are the increasing number of unpaid carers addressed?

Yes, but No: "Lost output from working age unpaid carers looking after the working-age sick"??

A revised article. An article in the CAPE Section of Carer Mentor: Empathy and Inspiration. [Care, be Aware, Prepare & Engage. (CAPE). Dispelling the myth that Carers are Superhuman. ]

When we’re listening to the UK’s Autumn Budget on November 26, I urge everyone to consider the news from an unpaid carer’s perspective, and how the welfare state, and ‘economic inactivity’ are being framed.

There’s an ageing population, people living longer, an exhausted, overburdened, but under-resourced NHS, and social care reforms are not yet in place. These are the facts that unpaid carers are very familiar with, and yet news reports and the general public wonder why more people are becoming “economically inactive.”

Surely people know that more of the working population are leaving work or reducing their working hours because they need to care for their parents, and/or other friends or family who are sick or disabled of any age.

Ask an unpaid carer about social care or paid carer support, and they’ll tell you about how the good ones are over-worked, underpaid and can only do a short call, e.g. 15 minutes, and can’t promise to get to you at a specific time. You don’t want to hear about the bad ones.

The over-40s are leaving/reducing work at the time when they’re considered to be at their most productive, because they’re using their time, and mental labour to care for others. This includes

the direct hands-on tending to needs,

the behind-the-scenes facilitation, project managing, and interfacing with

the fragmented, mainly digital, health and social care systems.

all things related to home, finances, food and necessities

as well as standing at the threshold between loved ones and everyone else: the buffer, medical translator, explainer of needs and wishes, defender and advocate for loved ones who cannot speak for themselves.

So, when I first saw a BBC news report (November 5th), I felt I had to dig into the ‘Keep Britain Working’ independent report and its analyses.

I was ardently hoping that somewhere in the ‘system dynamics’ there would be some reference to Carers UK's State of Caring report (October 2025) and that the voices of 5.8 million unpaid carers in the UK, would be represented.

We can work more productively; be focused and committed, when we know our loved ones are safe and cared for. When work policies enable us to take a family member to a medical appointments without repercussions. Or flexible work cultures enable us to work remotely, or care for a loved one post-operatively,

Not addressing the journey that leads people to become full time unpaid carers, or how to enable them to stay/return to work, may force more people to choose family needs over work. Even in financially challenging times, and especially when the NHS plans involve a shift from hospitals to the community, while systems are still fragmented.

An Unpaid Carer’s Context:

Working full-time for an employer, an organisation, or yourself, while you’re worried and caring for someone you love, is stressful. Orchestrating caregiving in a fragmented care system compounds the burden and pressure on individuals.

Caregiving is mental and emotional labour intertwined with project management, where you have limited or no decision-making power! Navigating your own vulnerabilities through this is one thing; coaching and managing those worries and vulnerabilities of a sick or frail loved one is something else.

Five evidence-based insights:

Carers are reducing their working hours or leaving work. 1

The intensity of caregiving has increased. This is significant because of the devastating impact that substantial unpaid care of over 20 hours per week can have on carers’ health, well-being and ability to juggle work and care.2

The number of unpaid carers will rise because the health and social care system remains fragmented and under severe strain as it prepares for a major shift from hospital to community care. Plus, social care reforms have been delayed3

The increased need for care has outpaced infrastructure investments and policy reforms. 4

The BBC news report on November 5th, 2025

Nov 5th The BBC reported: “The number of sick and disabled people out of work is putting the UK at risk of an “economic inactivity crisis” that threatens the country’s prosperity, according to a new report.

There were 800,000 more people out of work now than in 2019 due to health conditions, costing employers £85bn a year, according to the review by former John Lewis boss Sir Charlie Mayfield.

The problem could worsen without intervention, but Sir Charlie Mayfield, who will lead a taskforce aimed at helping people return to work, said this was “not inevitable”.

The BBC news article was based on the independent ‘Keep Britain Working’ Report published that day.

Sir Charlie Mayfield is the Lead Reviewer: the report and letter to the Secretaries of State for the Department for Work and Pensions, and Department for Business and Trade

Why is the focus only on the sick and disabled as the economically inactive?

Employer policies, inclusive work environments and reasons that lead anyone to becoming economically inactive, require consideration.

The ‘purpose and scope’ of the review, as set out in the Terms of Reference on the one hand requests “a discovery phase, with the aim of understanding the characteristics and drivers of rising levels of inactivity and ill health”, but on the other hand precludes a focus on disability and ill health, to the exclusion of other drivers of inacitivity that may be positively impacted by new policies and initiatives by employers and the government.

My questions and the answers I’ve drawn from the reports:

Where are the unpaid carers in the Keep Britain Working Report, and how are they being included, if at all, in the recommendations?

Unpaid carers are named in the report, but only as a subgroup:

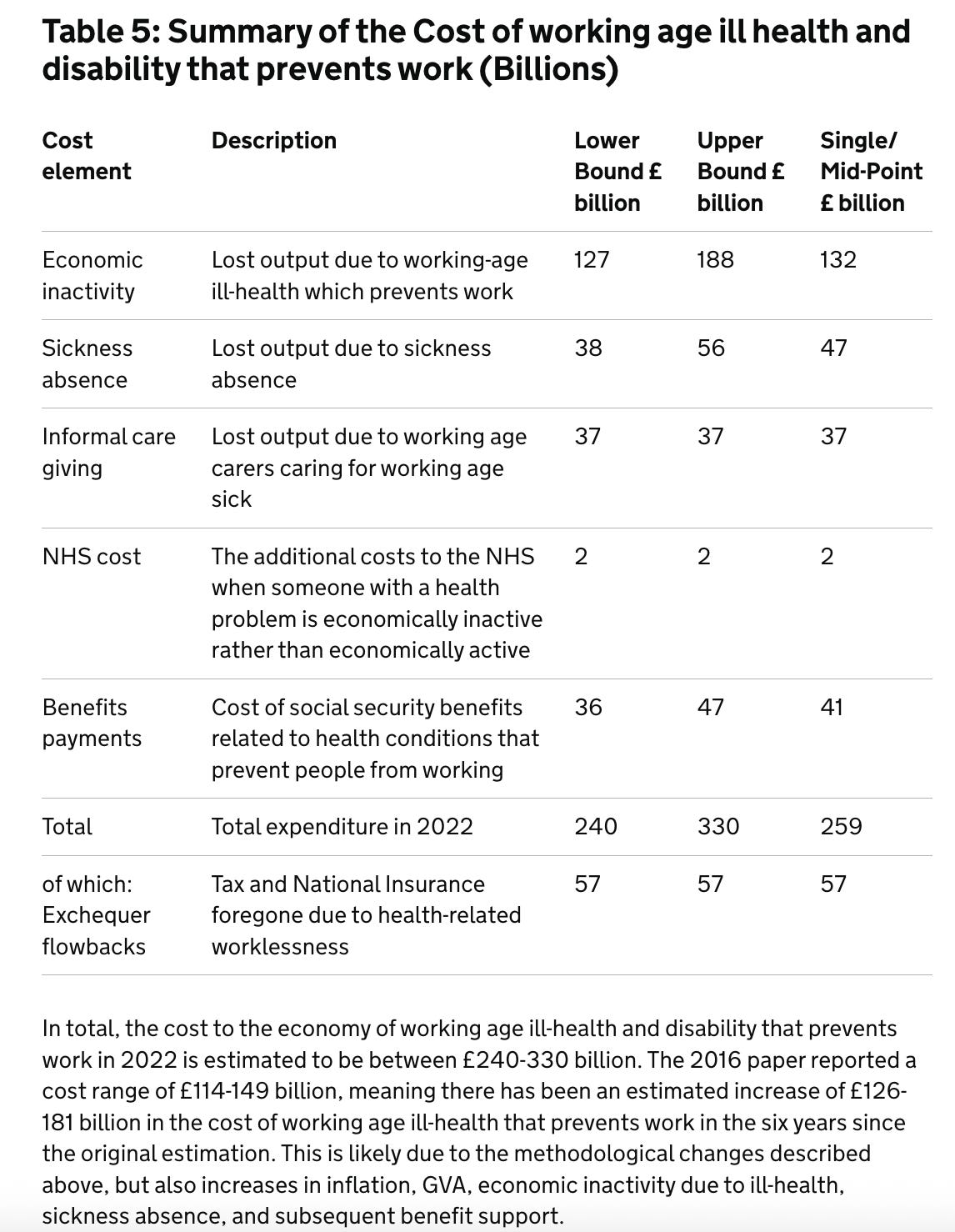

Informal caregiving: £37 billion lost output due to “working-age carers caring for working-age sick” (Table 5: Summary of the Cost of working-age ill health and disability that prevents work (Billions)) Footnote 6

My hypothesis: The task force's work and recommendations are solely focused on ‘the working age sick’. Using the working assumption that enabling the working-age sick to return to work will, in turn, result in a possible £37 billion economic input from informal caregivers returning to work, too.

Unpaid carers who are caring for the sick or elderly (non-working-age sick) are not a focus of this analysis, despite the Carers UK State of Caring report highlighting the increasing number of people leaving/reducing work and the increased intensity of caregiving.

Unpaid carers, and their reasons for reducing hours or leaving work, are omitted in the ‘System Dynamics’ analysis on page 18 of the report. There is an opportunity for the review and employers to consider preventing further loss of unpaid carers from becoming economically inactive

Does the report assess the impact of delaying social care reforms on the rising numbers of ‘economically inactive’ people? Not that I can see

Does the report leverage the State of Caring Report (October 2025) by Carers UK to identify the reasons why the working population may choose to reduce their hours to care for loved ones? (Especially in light of the new healthcare plans to shift care from hospitals to the community?) Not that I can see

How will the task force include insights from unpaid carers and carer organisations to prevent further loss of ‘economically active’ people from the workforce? Unknown. My interpretation of the report is that the focus will not be on unpaid carers but on people of working age who are sick, ill, or disabled. The assumption being that if these people return to work, unpaid carers who are currently caring for them, can also work.

To answer my questions, I followed the data down a rabbit hole

I’ve done my best to decipher the data as a member of the public and an unpaid carer interested in understanding how this report could offer future opportunities to unpaid carers.

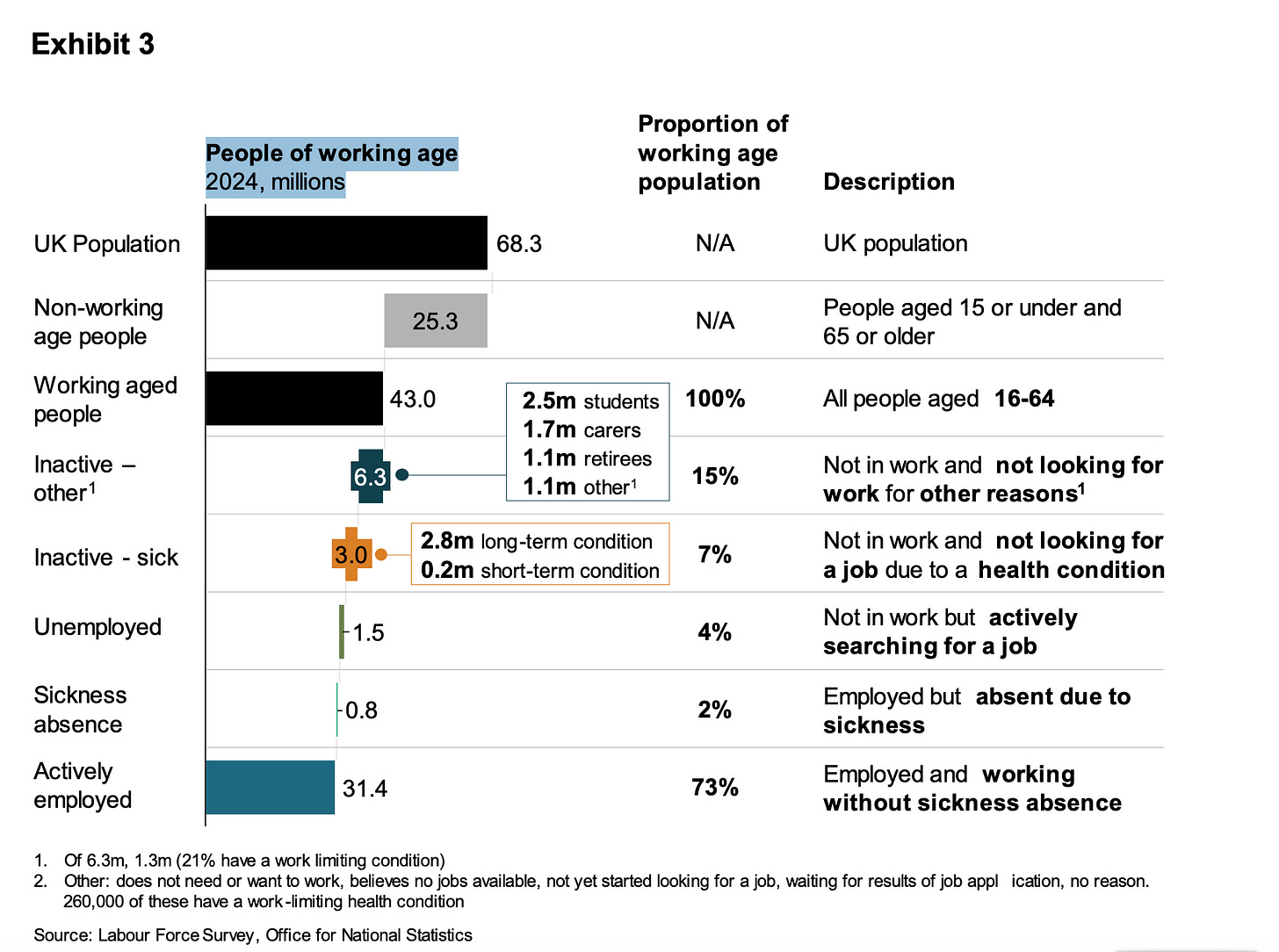

The report uses ONS data from 2024, but it focuses on 3 million people who are ‘Not in work, and not looking for a job due to a health condition’.

Carers (1.7m) are highlighted here but seem to be deprioritised in the analysis as ‘Inactive-other’ because they are ‘Not in work and not looking for work for other reasons’5 (see the footnote)

The report focuses on these 3 million people and suggests that the

‘wider impact and burden on society is equally unsustainable.’

Why focus only on the 3 million who are sick? There are potential opportunities of supporting unpaid carers and preventing them from reducing their hours/leaving work.

Moreover, while unpaid carers are statistically accounted for, I could only find this reference to them as a subgroup: ‘unpaid carers – many of working age – add hidden costs in lost productivity and foregone earnings through stopping work to care for those with health conditions.” (see below)

Impact on Society

48. The wider impact and burden on society is equally unsustainable. Economic inactivity caused by ill-health that prevents work is currently estimated to be costing the UK £212 billion a year[footnote 29] and rising, equivalent to around 7% of GDP, or nearly 70% of the total income tax we pay in the UK.[footnote 30]

Summary of the current cost of ill-health for society:

£132 billion – Lost output due to working-age ill-health that prevents work

£37 billion – Lost output from unpaid carers looking after the sick

£2 billion – Additional NHS costs of someone becoming economically inactive

£45 billion – Health-related benefits, forecast to rise another £20 billion by 2030[footnote 31]

49. These costs create substantial pressures across the system:

the NHS is forced into a reactive role – treating illness rather than supporting prevention. The OBR estimates inactivity adds measurable extra burden per person to NHS costs

rising benefit spend risks making the UK one of the highest spenders on health-related benefits among advanced economies[footnote 32]

unpaid carers – many of working age – add hidden costs in lost productivity and foregone earnings through stopping work to care for those with health conditions[footnote 33]

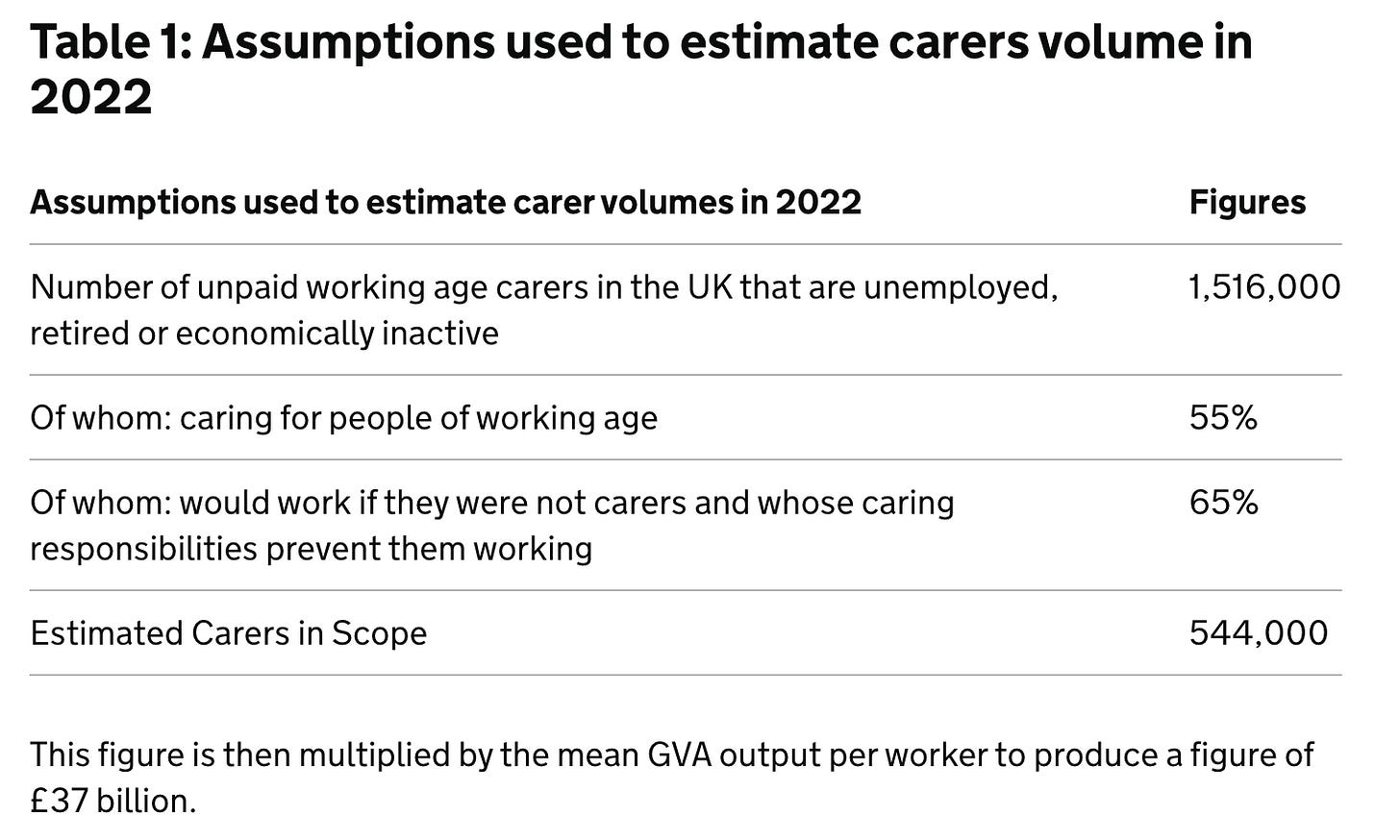

Where does this £37 billion come from? Department for Work and Pensions. Official Statistics The cost of working age ill-health and disability that prevents work Published 18 March 2025 calculated the lost output of what they’ve called a cost element of ‘informal caregiving’. Described as “Lost output due to working age carers caring for working age sick” 6 (see the footnote below)

Conclusion:

Unpaid carers are not the focus of the Keep Britain Working task force. They may be seen as being indirectly addressed in enabling working-age sick and economically inactive people to return to work.

Unpaid carers who are considered in the report: those who in 2022 were economically inactive, caring for people of working age. The carers, who ‘want to return to work but their caring responsibilities prevent them from working.’ Estimated to account for £37 billion in ‘lost output.’

The journey of unpaid carers to becoming economically inactive or returning to work hasn’t been addressed—yet?

Recommendation:

I urge Carers UK, Carers Trust, Mobilise and other unpaid carer-related organisations to elevate the findings and recommendations of the Carers UK State of Caring Report (October 2025) with the Keep Britain Working Taskforce.

A personal note:

I’m not an economist or social policy expert. It’s taken me hours to decipher the data and the report. I’ve done so because I believe that economic growth and the increasing numbers of unpaid carers in the UK are interrelated issues.

Footnotes:

I have included direct references, content and information from the publicly available reports, publications and Labour Force Survey. I’m not aware of any restrictions to reproducing this data here.

Carers UK State of Caring Report October 2025 (n= 10’539)[Executive summary page 8. ]

“Carers often find that as their caring responsibilities increase, they find it more difficult to combine caring with paid employment, and many have given up work or reduced their working hours. 35% of carers who are employees have reduced their working hours, and a fifth (20%) of carers who are employees have moved from working full-time to working part-time.

Giving up work to care or reducing working hours can make it harder for carers to save for the future or pay into a pension. Three quarters (74%) of carers said they are worried about the impact that their caring role will have on their finances in the future, and a quarter of carers (24%) said they had cut back on, paused, or stopped paying into a pension because of the financial costs of care.”

The intensity of caregiving increased between 2011 and 2021.

They may not call themselves “Unpaid Carers’ but they are dedicating more time to caring, reducing/leaving “economic activity”. Census 2021 versus 2011 data shows an increase in substantial unpaid care in England and Wales

Carers UK Press release Jan 2023:

152,000 rise in number of carers providing over 50 hours of care to just over 1.5 million.

Over a quarter of a million rise in number of unpaid carers providing 20-49 hours of care.

Surprising overall drop in number of carers from 5.8 to 5 million unpaid carers.

Today the Office for National Statistics has published Census 2021 data about unpaid carers which showed growing intensity of care across England and Wales.

Unpaid carers provide help and support to a relative or friend who has a disability, illness, mental health condition or who needs extra help as they grow older.

There is a distinct increase in the number of people providing substantial care, of 20-49 hours a week (260,000) and 50 hours a week (152,000) between 2011 and 2021 and a deepening of the amount of care provided over time. This is significant because of the devastating impact that substantial unpaid care of over 20 hours per week can have on carers’ health, wellbeing and ability to juggle work and care.

However, despite the pandemic, surprisingly the overall number of unpaid carers has fallen from 5.8 million in the 2011 Census to 5 million in the 2021 Census across England and Wales, mostly through a reduction in the numbers of people providing lower hours of care.

The ONS suggests a number of reasons for this, including changes in the nature of caring during the pandemic and the high levels of deaths during the pandemic. However, it also suggests that the change in question framing could have made a difference. Whilst the 2011 Census question mentioned providing unpaid care for family, friends or neighbours, the 2021 question referred to caring for anyone. This will have had an impact because people don’t recognise themselves as unpaid carers.

With a shift from hospital to community care and the absence of social care reforms, the number of unpaid carers will rise.

Social care reforms are delayed. On Jan 3, 2025, the government announced an independent commission to reform adult social care, chaired by Louise Casey. Split into two phases, this cross-party commission will report firstly in mid-2026 and then will set out a longer-term plan by 2028’

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) has warned in its annual State of Care report that the health and social care system remains fragmented and under severe strain as it prepares for a major shift from hospital to community care.

The increased need for care has outpaced infrastructure investments and policy reforms.

You can read the response of the County Councils Network here, and Melanie Williams, President of ADASS (Directors of Adult Social Services (UK)) here. Here’s an excerpt:

“Unfortunately, the timescales announced are too long and mean there won’t be tangible changes until 2028. We already know much of the evidence and options on how to reform adult social care, including our independently commissioned Time to Act report, and worry that continuing to tread water until an independent commission concludes will be at the detriment of people’s health and wellbeing. (Melanie Williams)

CQC warns lack of investment in community services threatens shift towards care outside hospital – and risks ‘erosion’ of care quality

The health and social care system remains fragmented and under severe strain as it prepares for a major shift from hospital to community care, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) has warned in its annual State of Care report.

While there is some encouraging evidence of innovation, community services need significant investment in both capacity and capability to deliver the transformation in people’s care called for in the government’s 10 Year Health Plan for England.

Without more support to help community services deliver the vision of the plan, there is real risk of erosion in care quality, with people struggling to get the care they need and the most vulnerable groups likely to be hit hardest through longer waits, reduced access and poorer outcomes.

The report also highlights longstanding inequalities with some groups of people – including older people, people with dementia, people with a learning disability, and those with complex mental health needs – more likely to struggle to navigate services, often meaning their families and unpaid carers carry increasing burdens.

Keep Britain Working Review Discovery Document (March 2025)

The report uses ONS data from 2024, but it focuses on 3 million people who are ‘Not in work, and not looking for a job due to a health condition’. Carers (1.7m) are highlighted here but seem to be disregarded as ‘Inactive-other’ because they are ‘Not in work and not looking for work for other reasons’

Page 10 Exhibit 3 Source: Labour Force Survey, Office for National Statistics

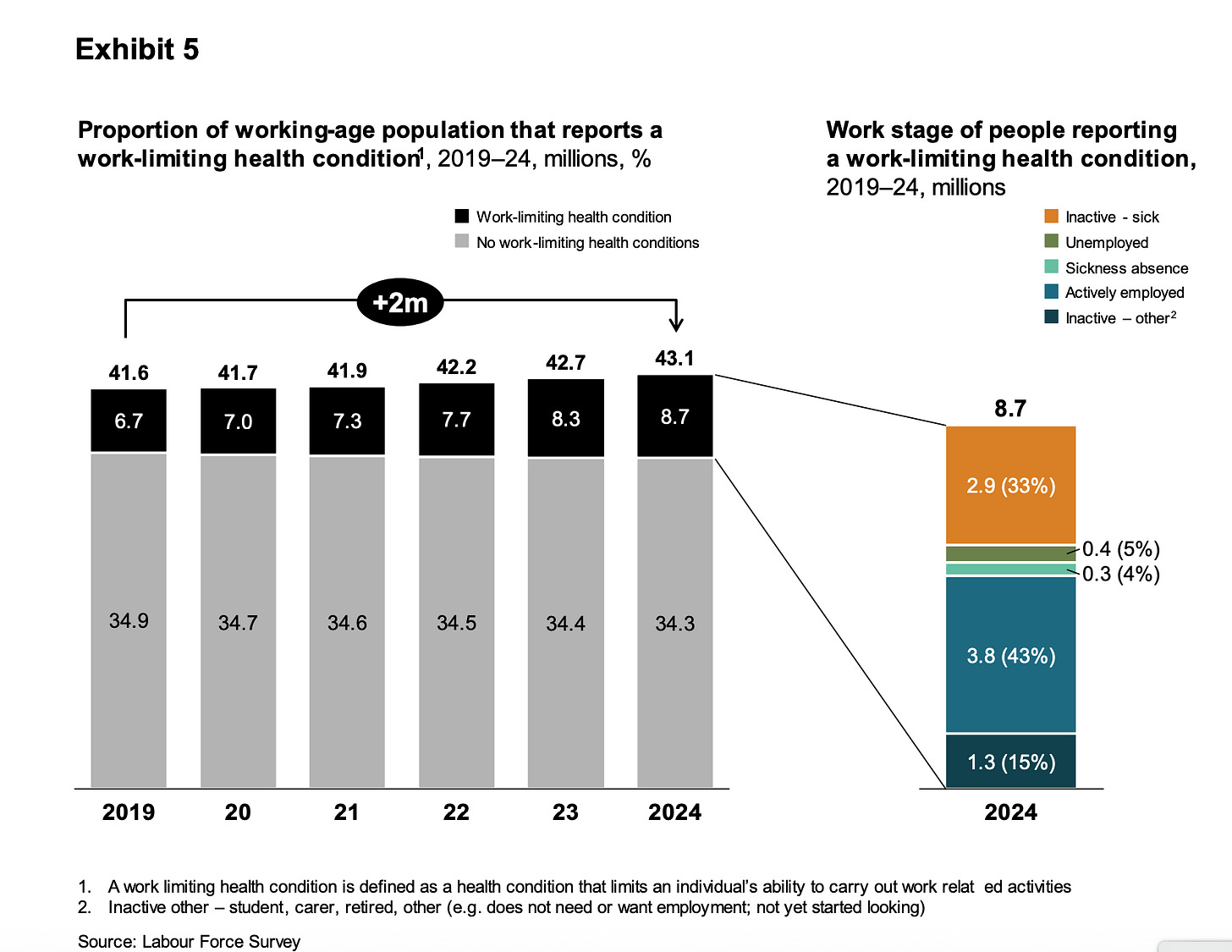

Page 12 Exhibit 5 Source: Labour Force Survey:

Page 12 point 28

28. There are now around 8.7 million people across the working-age population who report having a work-limiting health condition. There are three key take aways from these trends in the context of this review:

i. More people are in work with a work-limiting health condition than are economically inactive because of one. We have seen a significant growth in the numbers of people managing these conditions in the workforce.

ii. Based on these figures it is likely employers already have members of their workforce who are living and working with a work-limiting health condition. Health and disability are just as much an in-work issue as they are an economic inactivity issue.

iii. Of the 4.2 million economically inactive individuals, only 2.9 million report being economically inactive for sickness reasons. The remaining 1.3 million give their reason for economic inactivity as being carers, students or early retirees living with health conditions. This highlights how improving the way the workplace supports individuals to manage their health, and addresses the barriers faced by disabled people, could help people in other categories of economic inactivity to return to work.

Page 18 System Dynamics

Prevention, of both health and disability challenges arising in the first place and of people falling out of work, is very likely to be better than ‘cure’.

It is therefore a priority for the review to consider measures and initiatives to prevent people from falling out of work, protecting their health and ensuring support is readily available.

Department for Work and Pensions. Official Statistics The cost of working age ill-health and disability that prevents work Published 18 March 2025

A core part of the estimates for this work is the Gross Value Added (GVA) per person. GVA is measured as an average (mean) value per filled job and can be thought of as the individual’s job contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It encompasses more than the wage as an output, quantifying the wider value the individual brings to a business. It is reasonable to assume that the value of an individual’s output should exceed their wage, considering employment costs and a profit margin.

The GVA output per worker was £68,818 for the UK in 2022[footnote 3], [footnote 4]. This analysis also estimated a GVA figure for disabled people that may be more appropriate to apply to individuals with known ill-health. The GVA for a disabled worker is estimated for this analysis through multiplying mean GVA for all workers, by the ratio of median hourly pay of disabled workers[footnote 5] to mean hourly pay for all workers (excluding overtime)[footnote 6], [footnote 7]. Using this, the estimated median annual GVA for a disabled person was £46,513 in 2022.

It is worth noting that GVA varies from region to region[footnote 8], and that ill-health that relates to work also has regional differences[footnote 9]. However, this adds a complexity to the analysis that is beyond the scope of this analysis as regional splits are not available for the wide range of data required.

Lost production due to informal caring

It is estimated that there were 5 million unpaid carers in the UK in 2022[footnote 14]. Some of these carers will be working age, looking after someone who is working age, and out of work due to these unpaid caring responsibilities, and thus meet the definition of ‘cost of working age ill-health that prevents work’. In this instance it is the carer who is prevented from working, rather than the individual with the ill-health/health condition. The population of carers relevant to the economic cost of working age ill-health are: i) carers of working age who are out of work; ii) caring for people of working age; who iii) would work if they were not carers and whose caring responsibilities prevent them working.

All these conditions must be met to be relevant for the present estimations.

The calculation is based on the number of working age unpaid carers that are currently unemployed, retired or otherwise economically inactive[footnote 15]. The NHS Digital survey (2023 to 2024) can be used to determine the distribution of working age carers caring for someone of working age[footnote 16], and the distribution of out-of-work working age carers who are not in employment, because of their caring responsibilities, rather other reasons, such as retirement[footnote 17], [footnote 18]. Taking these distributions, around 550,000 carers were out of work due to working age ill-health (see Table 1).

The 2016 paper produced a figure of £1 billion. The methodology used in this work has had slight refinement, so the difference is in part due to this. The 2016 paper took the percentage of the whole carers population who looked after someone who is working age, rather than the percentage of working age carers who looked after someone who is working age. This was also the case for the split of carers who are out of work due to their caring responsibilities. The key driver of the increase since the 2016 estimates is that the 2016 method assumed that only 5% of those being cared for would likely return to work, and that 95% of carers who fit the criteria would never be able to return to work as they would have to look after someone. The cost was therefore reduced by 95%. However, as there is still a cost to the care-giver and these estimates seek to consider all costs not just those which could be saved in practice, and as the informal care giver could enter employment if caring needs were addressed through social care, this analysis does not exclude any informal care givers that meet the criteria set out above.

It is hard to disagree with anything you say here. My work has given me an insight into how anxiety provoking it is to have to project manage (as you say) the endless circles and frustrations of engaging with government agencies. The very real worries about payments being stopped or curtailed add an extra anxiety to an already difficult situation. I am also very interested in how the seeming need to avoid up front costs of preventive measures just exacerbates so many areas of ill health or functional difficulties. And pushing these costs further down the line has a snow ball effect, they grow and grow and then when people reach crisis point, there is insufficient response, lack of financial support and utter confusion. I think there is a broad brush suggestion that 'unfit to work' equals 'malingering' and that forcing the sick back to work is the answer (I use forcing rather than facilitating because that is how is feels to the people I work with). There is no recognition of the wide spectrum of what unfit means, and no recognition of the adverse impact on the mental health of the carer who gives up their work, their plans, their aspirations to care for a loved one. Like many social issues, we are in the position, through lack of foresight or financial commitment or both, of tinkering around the edges, rather than having a coherent, future proof strategy. I could say the same of the NHS and I daresay the same is true of education.

Wow! Victoria you have worked so hard on this. Maybe one of the reasons unpaid carers don't appear as part of this report is that unpaid carers save the country billions, and if social care isn't ever going to be made a priority, then it is felt better to keep carers proping up the system rather than helping them to get back into work?